Monday, June 18, 2001

Up at 7:00 am. Breakfast of pizza bread, toast, yogurt, miso soup, green tea, and juices. Left at 8:30 with Yuriko and Aunt Kyoko, and overnight bags.

At the subway, Tamiko discovered she had brought the used-up Metro card, instead of a new one (they both had the same design). But Aunt Kyoko had a handful of one-way tickets and gave her one.

At Ikebukuro, we waited for a JR train to Nikko. And we waited for Aunt Michiko, and Aunt Kikuko, to arrive to accompany us on this trip!

|

Disciplined commuters line up, leaving space for

riders to disembark from the train

|

On this train trip, we headed north out of Tokyo, and saw different scenes. Still lots of new construction going on. Then on to the plains and the rice paddies. Here and there among the rice paddies were vegetable garden plots and flower gardens. Billboards also dotted the paddies.

Aunt Kikuko brought a package of raisin cookies for our snack, just like the kind from our childhood (like a raisin jam between two soft crackers).

The train took us to Onitsuyama, where we changed to a local train to Nikko. We had time to check out a department store, but Kent had no success finding an English-language newspaper, which had not been a problem anywhere else we had been.

The train to Nikko took a half-hour. We then took two taxis to the ryokan. The taxis took us past a small bridge which was totally covered by scaffolding and tarps. This was Shin-kyo, the Sacred Bridge, reserved for the exclusive use of the shogun and the imperial family, an arched red lacquer bridge.

The Nikko Ryokan Senhime Monogatari was a large modern building at the base of a green mountainside. Aunt Kyoko checked us in.

Long Lunch

We were sent up the street to a soba shop for lunch. The one little old lady seemed overwhelmed by our group, and she had other customers as well! You could hear her banging pots in her little kitchen, but our meal took a long time coming. Fortunately, the shop also had ceramics for sale, and we were able to browse the display from our seats.

Even the aunts were saying the old lady must be preparing the noodles from scratch; it was taking so long. Eventually we did get our soba noodles with mushrooms, or buckwheat noodles.

We also had to wait to pay the bill, as the old lady did have other customers, and the postman came in to distract her even more.

Finally we began our ascent of the hill opposite the ryokan. The aunts knew where to purchase the combination tickets for the Toshu-gu temple complex.

Tosho-gu

Tosho-gu was built by Iemitsu, the third shogun, and grandson of Ieyasu Tokugawa, who was first in line. Ieyasu was a powerful warlord who won the battle at Seki-ga-nara in the mountains of south central Japan in 1600, to make him the undisputed ruler of Japan. He died in 1616, leaving a rich dynasty to last 252 years, keeping the country peaceful, prosperous, and united. According to Buddhist custom, a year after his death, Ieyasu was given an honorific name to bear in the afterlife. The name was Toshu-Daigingen, meaning Great Incarnation Who Illuminated the East. The imperial court in Kyoto declared him a god.

Iemitsu built the temple based on Ieyasu’s will which called for a mausoleum in Nikko, then a forest of tall cedars. The tomb was meant to inspire political awe and to manifest the power of the Tokugawas; a legacy stating his family’s right to rule.

It took the labor of 15,000 men over two years (1634-36). First-rate craftsmen and artists were brought from all over Japan. Every surface was decorated in intricate detail, shimmering with 2,489,000 sheets of gold leaf. Roof beams and rafters ended in dragon’s heads, lions, and elephants. There were friezes of phoenixes, ducks, monkeys. There were inlaid pillars, red-lacquer corridors; everything a 17th century warlord would consider gorgeous. The inspiration was Chinese.

After buying the tickets, we headed straight uphill along an avenue lined with giant cedar trees.

|

| Avenue lined with cedar trees |

We bypassed lesser, but nevertheless large temples, until we came to the stone torii entrance of Tosho-gu.

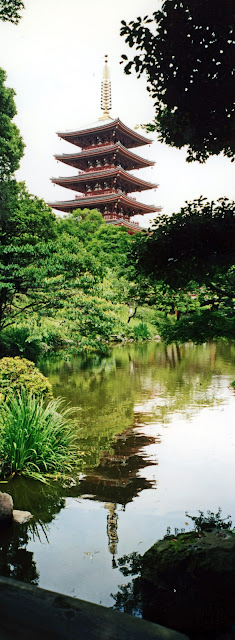

To the left was a 5-story pagoda, rebuilt in 1818. The first story was decorated with the animals of the twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac. Much of the pagoda was intricately carved and painted in bright colors. We could not discern the 3 hollyhock leaves of the Tokugawa crest.

From the torii, we climbed stone steps to the front gate, the Nio-mon, or the Gate of the Deva Kings, a fearsome pair of red-painted guardian gods.

|

| Nio-mon/Gate of the Deva Kings with Korean dogs |

Because they were red, we assumed they were actually Emmas, or gods of the underworld. On the back side of the gate stood a pair of Korean dogs.

"Hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil"

Once through the Nio-mon gate, the path turned left. The first building we came to was the stable.

|

| Oumaya/Sacred Horse Stable |

According to Shinto tradition, the stable housed a white horse (a gift from Korea?). This one was real.

|

| The white horse |

But the stable is better known for its carved panels, decorated with pine trees and monkeys. In the center panel were the three famous monkeys: “Hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil.” This panel has become a symbol of Nikko.

|

| Hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil |

The path turned right at a granite fountain for purification by washing the hands and rinsing the mouth before entering the shrine. Next to the fountain was the Kyozo, or Sutra library, containing 7,000 Buddhist scriptures, kept in a 20-foot high revolving bookcase.

|

| Kyozo/Sutra Library |

It was not open to the public, but the building as well as the roof over the fountain were decorated with carvings and gold leaf.

We passed through a bronze torii, and climbed more steps. On the right was a belfry, and standing in front to the right was a huge bronze candelabrum. On the left was the drum tower, fronted by a large bronze revolving lantern. These bronze items were gifts from the Dutch in the 17th century. At the time, they were the only country allowed to trade with Japan. The gifts were sent as a token of esteem in order to keep their monopoly.

|

| Tosho-gu: Kyoko, Kikuko, Yuriko, Tamiko, Brynne, Michiko |

Yomei-mon

We were directed up more stairs to the Yomei-mon, or Gate of Sunlight, the centerpiece of the shrine and a National Treasure.

|

| Yomei-mon/Gate of Sunlight detail |

It was also called the Higurashi-mon, or Gate of the Twilight, implying that you could look at it until dusk, in all its detail. It was 2-stories high, 36-feet tall, with twelve columns. The beams and roof brackets were carved with dragons, lions, clouds, peonies, Chinese sages, and demi-gods painted in vivid hues of red, blue, green, and gold. To the right and left of the gate were galleries, or paneled fences, running east and west for 700 feet. These were carved and painted with a profusion of nature motifs including pine and plum tree branches, pheasants, cranes, and wild ducks.

Yomei-mon was the entrance to the inner sanctum. It was once the limit for lower samurai. Ordinary people were stopped outside the front gate!

Kara-mon

To the left in the inner sanctum courtyard, stood the Mikoshigura, the storeroom for the portable shrines, or palanquins, that process in the Tosho-gu Festival on May 17-18.

|

Mikoshigura/Storeroom for palanquins

and ceiling painting of angels playing harps |

The ceiling of the Mikoshigura has a painting by Ryokaku Kano of tennin, or Buddhist angels, playing harps.

Across the center of the courtyard was the Kara-mon, or Chinese Gate, the official entrance to the inner shrine. It is also a National Treasure, painted in elaborate detail with dragons and other auspicious figures. Extending to either side was the wall which enclosed the Hon-den, or Main Hall of the shrine.

To the right of the courtyard was the Goma-do, a hall where formerly prayers were offered for peace in the nation. Now couples can marry in a traditional Shinto ceremony with drums, reed flutes, and shrine maidens, for a fee.

The Inner Shrine

To the far right of the courtyard was the Sakashita-mon, or Gate at the Foot of the Hill.

|

| Sakashita-mon with Sleeping Cat |

Just above the gateway was another symbol of Tosho-gu, the Sleeping Cat. It is said to have been carved by Jingoro the Left-handed, a late 16th century master carpenter and sculptor who contributed to many Tokugawa-period temples, shrines, and palaces. We did not climb the 200 stone steps to see the tomb of Ieyasu.

Instead we took off our shoes, placed them in cubbyholes, and walked barefoot into the Hai-den, the Oratory. A priest gave a little talk in Japanese, as we looked around in the dim light at the lacquered pillars, carved friezes, and ceilings painted with dragons. Over the lintels were paintings of the 36 great poets of the Heian-period by Mitsuoki Tosa (1617-91), with their poems in calligraphy by Emperor Go-Mizuno-o.

Our group was then led into the Nai-jin, the Inner Chamber behind the oratory. The priest spoke again and had us bow several times. A mirror here represented the spirit of the deity (Ieyasu). A room to the right was reserved for the principal branches of the Tokugawa family, and a room to the left was for the chief abbot of Rinno-ji, who was always a prince in the imperial family.

Behind this chamber was the Nai-Nai-jin, the Innermost Chamber, where no visitors were allowed. In the heart of Toshu-gu, a gold lacquer shrine is where the spirit of Ieyasu lives, along with two others whom the Tokugawas decided were worthy companions. One was Hideyoshi Toyotomi, Ieyasu’s mentor and liege lord at the end of the 16th century. The other was Minamoto-no-Yoritomo, a military tactician and founder of the earlier Kamakura Shogunate, whom Ieyasu claimed as an ancestor.

Yakushi-do

We retrieved our shoes, and left the inner sanctum. We detoured to Yakushi-do, a building behind the drum tower. Yakushi-do holds a manifestation of Buddha as Yakushi Nyora, a healer of illnesses. Originally built in the 17th century, it was famous for the India-ink painting on the ceiling called “The Roaring Dragon,” first painted by Yasunoba Kano (1613-85). (See sidebar.) Yakushi-do burned in 1961 and was rebuilt. The present-day painting was done by Nampu Katayama (1887-1980).

Sidebar:

The Kano school is a 400-year family of artists founded in the late 15th century. Patronized by shoguns, the school specialized in Chinese-style ink painting, doing landscapes, decorative figures of birds and animals, for screens, paneled sliding doors, and interior walls of villas and temples.

A priest inside demonstrated the name of the painting by clapping together two prayer blocks, and the resulting echoing rumble was supposed to be the dragon roaring.

After taking some group pictures in the same area where risers stood for group pictures by professionals, and after taking some stones from the grounds of the temple for rock-collecting Mike S, we left Tosho-gu.

We followed a gravel path along a back wall of Tosho-gu. Ancient cedar trees towered around us.

Masatana Matsudaira, one of the feudal lords charged with the construction of Tosho-gu, planted cryptomeria (Japanese cedars) around the shrine and along all the approaches. It took more than twenty years (1628-1651) to plant over 15,000 trees, resulting in 22 miles of cedar-lined avenues. Fire and time have taken their toll, but thousands of cedars still stand creating solemn majesty.

Futarasan-jinja

A one-minute walk brought us to Futarasan-jinja, holy ground far older than the Tokugawa dynasty. The shrine was founded in the 8th century, and was sacred to the Shinto deities of Okuni-nushi-no-Mikoto, god of the rice fields and bestower of prosperity, his consort Tagorihime-no-Mikoto, and their son Ajisukitaka-hikone-no-Mikoto. Actually Futarasan is part of a three-part shrine, and is the Hon-sha, or Main Shrine. The other parts are Chu-gushi, the Middle Shrine, on Chuzenji-ko/lake, and Okumiya, the Inner Shrine, on top of Mount Nantai.

We entered through a side bronze torii into the central courtyard with the Hon-den, or Main Hall to the right, rebuilt in 1619.

We bought Y200 tickets to enter the area to the left rear of the shrine, to see the 7-foot tall antique bronze lantern.

|

| "Goblin" lantern |

Legend says the lantern would assume the shape of a goblin at night, and the deep nicks in the lantern were inflicted by Edo-period swords of guards on duty who were startled by the flickering shape in the dark. It showed the incredible power of the Japanese blade, a peerlessly forged weapon.

Ruling class samurai were apprenticed to masters to learn the arts of archery and swordsmanship. They demanded the finest equipment. It became a craft to make armor and swords combining beauty and function to the highest degree. Technical mastery surpassed Western methods, and Japanese swords were and are world-renowned. Today there are only a few inheritors of the skill, and they are now engaged in making knives, cutlery, and farming tools (see sidebar).

Sidebar:

Before Japan closed its doors to the West in the late 16th century, the Spanish tried to establish trade in weapons made of the famous Toledo steel. The Japanese were politely uninterested, as they had been making incomparably better quality for 600 years. Early swordsmiths learned the art of refining steel from pure iron sand called tamahagane, carefully controlling carbon content by adding straw to the forge fire. The block of steel was repeatedly folded, hammered, and cross-welded to extraordinary strength, then wrapped around a core of softer steel for flexibility. At one time, there were 200 schools of sword-making. Swords were prized not only for their strength, but for the beauty of the blades and fittings.

We also saw a sacred spring, palanquins, a mini-Shin-kyo leading to a sub-shrine, a museum with a huge eight-foot sword (who could manage that?!).

|

| Sacred spring |

|

| Brynne on the mini-Shin-kyo/Bridge |

We left Futarasan-jinja through its Kara-mon, or Chinese Gate. We purified ourselves on the way out (gaijin are backwards!) at a fountain fed by a natural spring.

Daiyu-in

We followed the aunts to Daiyu-in, a Mausoleum and the second-most grandiose Tokugawa monument in Nikko. It was the final resting place of the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu (1603-51), who imposed the policy of national isolation on Japan that was to last for 200 years. He wanted to upstage his grandfather in the building of his shrine. The approach had six decorative gates.

The first was Nio-mon, or Gate of the Deva Kings.

|

| Deva King #1 |

|

| Deva King #2 |

Stone steps led to the second gate, Niten-mon, which was 2-stories with carved and painted images of guardian gods on both the front and back.

|

| View from stairs between heaven and earth |

Two flights of stairs, supposedly symbolizing leaving earth to go to heaven, led to a middle courtyard with a belfry to the right and a drum tower to the left.

Beyond was the third gate, Yasha-mon, named for the figures in the four niches, yasha, or she-demons.

|

| Yasha-mon detail, including a peony |

It was also called Botan-mon, or Peony Gate, for the carvings of peony flowers.

On the other side of the courtyard was the Kara-mon, or Chinese Gate, gilded and carved.

Through the Kara-mon to the Hai-den, or Oratory for a glimpse of a ceiling decorated with dragons, and Chinese lions on panels in the rear by two Kano school painters.

Koka-mon

We walked around the outside of the Hai-den, to see the Ai-no-ma, the anteroom or connecting chamber to the Hon-den, the Main Hall and innermost sanctum. The Hon-den is a National Treasure and housed a gilded lacquered Buddhist altar, in which resided a seated wooden figure of Iemitsu. Pictures of the altar decorated with paintings of animals, birds, and flowers could be seen in the Hai-den.

In the far right-hand corner of the grounds was the fifth gate, Koka-mon.

|

| Koka-mon |

It was built in late-Ming dynasty style, painted white with gilded doors. It was said to resemble the sea-world palace of a legendary sea turtle that was saved by a fisherman. Through this gate, which was not open, there were stone steps to a small oratory, and then a final climb to the sixth gate, the bronze Inuki-mon. This final gate led to Iemitsu’s tomb.

The Ryokan

We stopped for ice cream and drinks at a shop, which was then closing. We didn’t realize that tourist time was over!

|

| Nikko Pension |

|

| Our ryokan/inn Nikko Ryokan Senhime Monogatari |

We walked back to the hotel, and in the large open lobby sitting area, we were given green tea and sweets. The back of the lobby was a wall of glass, looking out into a walled garden with grafted azalea bushes bearing two colors of flowers. Above the wall you could see the green forested side of the mountain in a cloudy haze.

|

| Nikko Ryokan Senhime Monogatari lobby |

We were then escorted to the room, for more tea and sembei crackers.

|

| Room set up for a snack for seven people |

|

| Slippers for seven people |

We knelt to hear the hostess give her spiel, and made note of the fire escape. This ryokan room had an alcove with two twin beds. The back wall had large windows for a view on the mountain side.

All four sisters went to the women’s bath, and Kent went to the men’s bath on the first floor. Brynne and Tamiko took advantage of the room’s private bath.

The washlet in this ryokan had a basin on the back tank of the toilet, where water poured out of a faucet when you flushed, so that you could wash your hands.

|

| Washlet with "sink" |

When the others came back, they encouraged Tamiko and Brynne to go to the communal bath area, to try out the massage chairs, and the electronic foot massager, which they did.

A 16-item Dinner!

Since a table for seven diners was not practical in our room, we had dinner in a dining room on the first floor. Each of the private dining rooms had a client name written by the door.

In our yukatas, we sat three across from four at individual tables on our cushions with a seat back.

|

| Yuriko, Brynne, Kent, Kikuko, Michiko, Kyoko |

|

| Tamiko, Yuriko, Brynne, Kent |

|

| Kikuko, Michiko, Kyoko |

A pair of women came in to serve us. 1) A small cup held a plum wine cocktail. 2) A large green cube was wasabi-flavored tofu. 3) A green plum in a glass, on a plate with fried ebi, octopus, a cube of cooked egg, raspberry aspic, salmon paste with squash, and a shallot. 4) Another plate had a piece of Tochigi beef with a slices of mushroom, pumpkin, and tomato. You cooked the beef on your own mini-hibachi. 5) A bowl of white fish in broth with okra. 6) Especially cool was the frozen igloo housing the sashimi or raw fish.

|

| First course(s) 1-6 |

7) There was white asparagus, 8) a grilled white fish filet with a square of what seemed to be mint cheesecake. 9) Soba with makiyuba tofu, shrimp, and green beans.

|

| Second course: grilled white fish |

10) The tempura had shrimp, wonton, green pepper, and eggplant, and came in a basket.

|

| Third course: Tempura basket |

11) On a sterno burner, an egg was opened into broth with eel and greens, and was left to simmer until eaten. Finally, 12) clear soup, 13) pickles, 14) rice, 15) a yogurt concoction like Cool Whip, and 16) fruit including muskmelon.

Accompanied by green tea, water, and a weak local Nikko beer for Kent.

As we left our dining room, we ran into a group of men who appeared to have imbibed their fill. They were oohing and aahing over Brynne, but apparently Aunt Kyoko dealt with them firmly.

We returned to the room to see the futons and bedding had been laid out.

|

| Row of futons with Brynne |

There was only enough room for five futons, so Kent and Tamiko had the twin beds.

It rained hard that night.